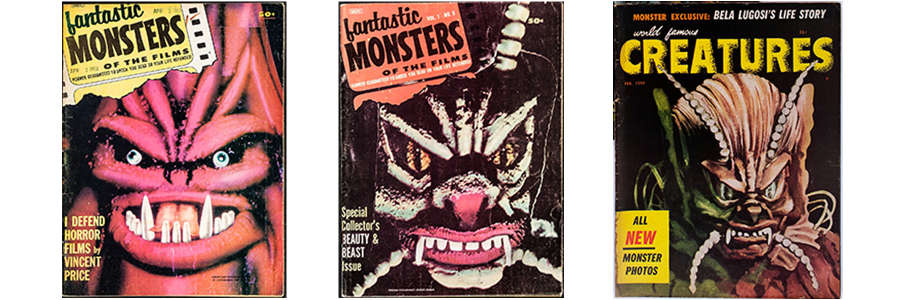

Few figures in cinematic history embody the phrase “doing more with less” quite like Paul Blaisdell, the visionary artist behind some of the most memorable creatures in 1950s and early 1960s low-budget horror and sci-fi films. Born on July 21, 1927, in Newport, Rhode Island, Blaisdell’s love for the macabre and artistic creativity set the stage for a career that would leave a lasting impact on the genre.

Early Life and Creative Beginnings

As a child, Blaisdell showed an early fascination with the eerie and otherworldly. His talent for illustration and design led him to study at the New England School of Art and Design, where he honed the skills that would later define his career. While many special effects artists relied on large teams and expansive budgets, Blaisdell excelled at working with limited resources, transforming everyday materials into creatures that thrilled—and occasionally terrified—audiences.

The Big Break: AIP and the Birth of DIY Movie Monsters

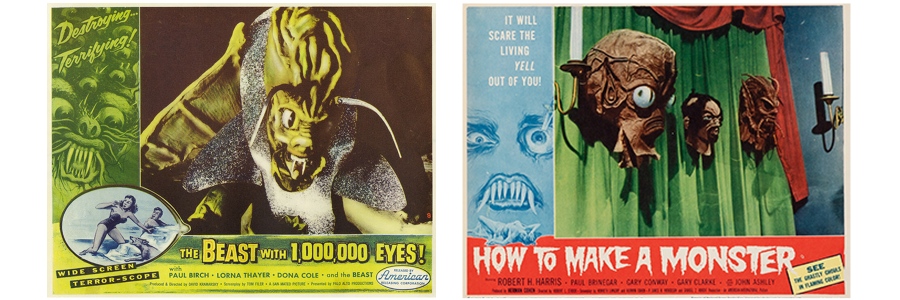

Blaisdell’s breakthrough came when he partnered with American International Pictures (AIP), a studio renowned for churning out low-budget genre films. His first major project, “The Beast with a Million Eyes” (1955), showcased his knack for ingenuity. Working under tight budget constraints, Blaisdell crafted the creature using common household items like egg cartons and wire. The result? A minimalist design that, while rarely shown on screen, cemented Blaisdell’s reputation as a resourceful artist who could create magic with a shoestring budget.

Cult Classics and Iconic Monsters

Blaisdell quickly became AIP’s go-to special effects maestro, crafting monsters for films that have since achieved cult status. His creations appeared in classics such as:

- “The Day the World Ended” (1955): A post-apocalyptic thriller featuring Blaisdell’s handmade mutant costume, which he personally wore during filming.

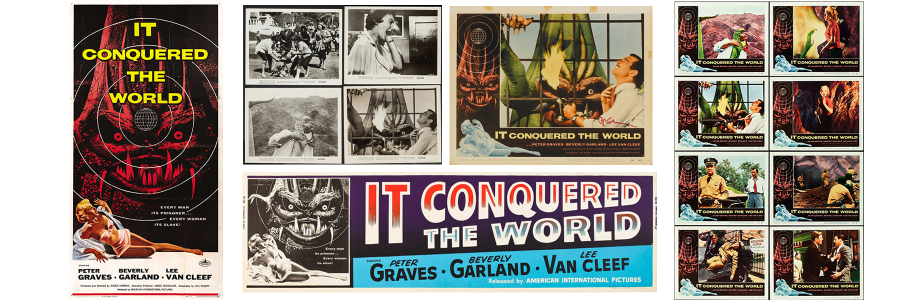

- “It Conquered the World” (1956): The now-infamous “walking cucumber” alien, both mocked and adored by fans for its campy charm.

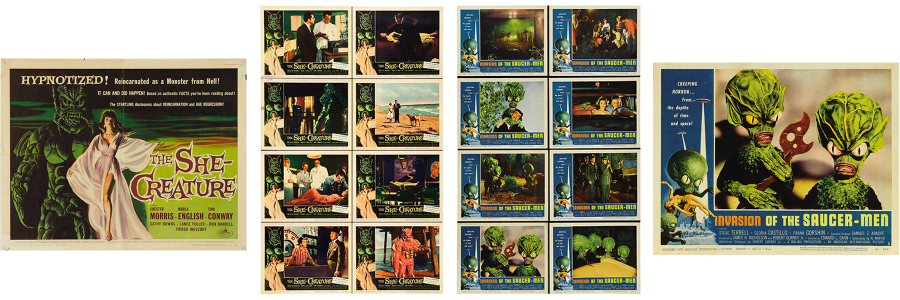

- “Invasion of the Saucer Men” (1957): Featuring oversized “little green men” with bulging eyes—an image that has become synonymous with 1950s sci-fi.

Each creature reflected Blaisdell’s unique ability to merge imagination with practicality, turning rubber, latex, and found objects into memorable movie monsters.

Challenges and Disillusionment

Despite his groundbreaking work, Blaisdell’s career was cut short by the industry’s rapid evolution. By the early 1960s, advances in special effects and the rise of bigger budgets left little room for his handcrafted approach. Disheartened by the lack of recognition and dwindling demand, Blaisdell left the film world behind. He passed away on July 10, 1983, at the age of 55, but his legacy lives on as a testament to creativity under pressure.

Behind the Monsters: Fascinating Facts

Take a closer look behind the scenes of some of Blaisdell’s most iconic films:

- “The Beast with a Million Eyes” (1955)

- Last-Minute Monster: The script originally envisioned an invisible alien. Blaisdell was brought in late to create a physical creature using scraps, cementing his status as a resourceful artist.

- Minimal Screen Time: The creature’s limited budget led to brief appearances, adding to its mystique.

- “It Conquered the World” (1956)

- Cucumber Controversy: Blaisdell designed the alien to be menacing, but its cucumber-like shape made it a camp classic instead.

- Transportation Trouble: The cumbersome monster required a small team to maneuver it, resulting in its signature slow shuffle.

- “Invasion of the Saucer Men” (1957)

- Hand-Puppetry Magic: Close-ups of the aliens injecting victims with alcohol were achieved using hand puppets, adding an unsettling touch to the film.

- “The Angry Red Planet” (1959)

- Martian Menace: Blaisdell’s bat-rat-spider-crab monster was designed to shine under the film’s unique red-tinted “Cinemagic” process.

Why Blaisdell’s Work Still Matters

Paul Blaisdell’s monsters may have emerged from tight budgets and limited resources, but they embody the heart and soul of mid-century B-movie cinema. His creatures continue to captivate fans and inspire filmmakers, proving that ingenuity and passion often trump lavish budgets. Blaisdell’s story is not just a history lesson—it’s a celebration of the creative spirit, and a reminder that even the most modest beginnings can leave an indelible mark.